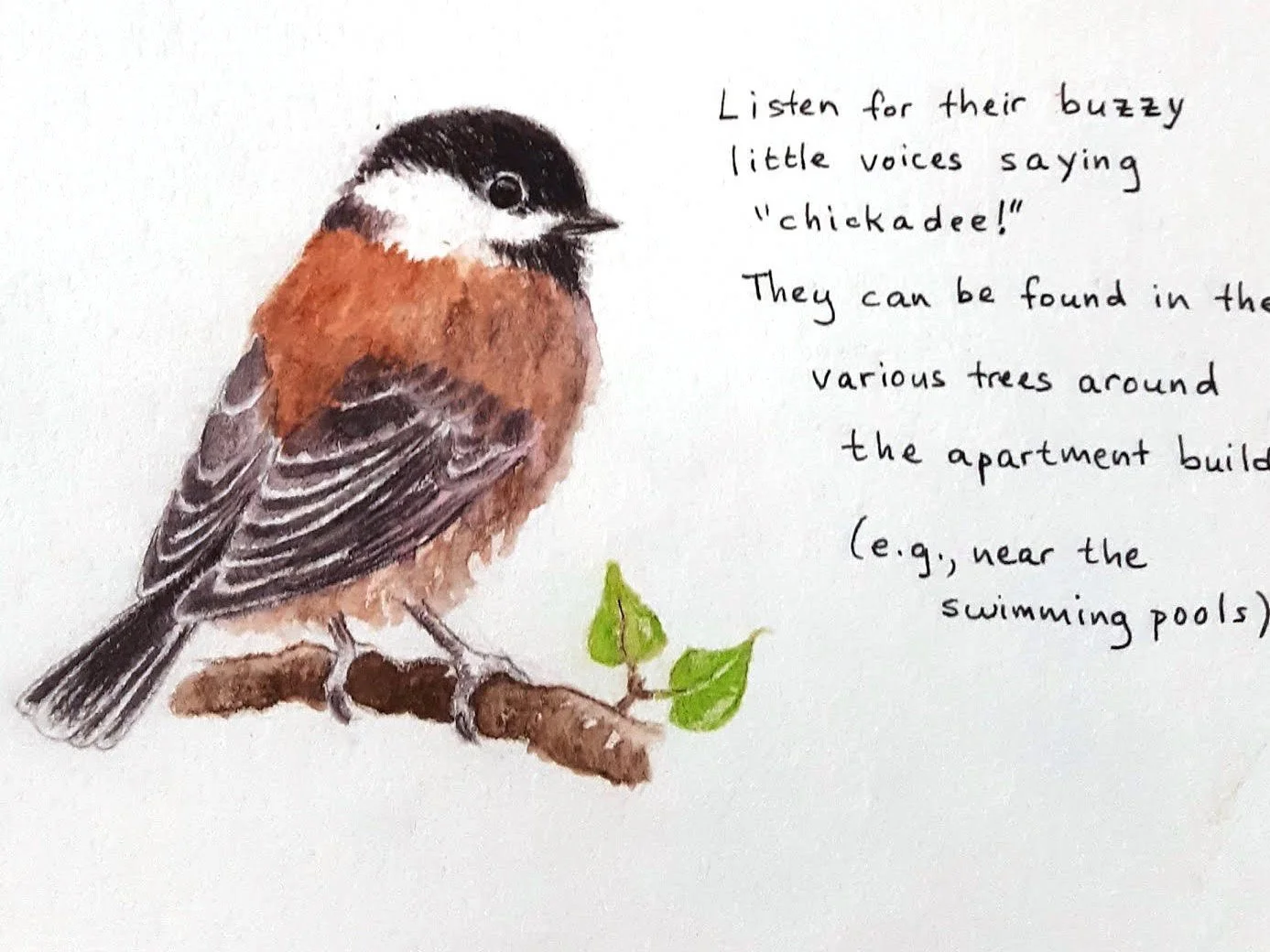

Cedar Waxwing

by Dave Zittin

We know it is winter at our place when flocks of Cedar Waxwings appear from time to time on our black walnut tree. Frequently we will see more than 25 Cedar Waxwings at a time high on the tree, doing their whistle call and looking very much like tree ornaments.

There are only three waxwing species in the world: The Cedar Waxwing, the Bohemian Waxwing, and the Japanese Waxwing. Waxwings are in the family Bombycillidae (bombux=silk). Their closest cousins are the silky flycatchers, in the family Ptilogonatidae which includes the Phainopepla. Both families are fruit eaters and have smooth outer feathers that give them a silky appearance.

Notice the black face surrounded by a thin white line, the yellow-tipped tail and the yellow belly. Photo by Erica Fleniken.

Cedar Waxwings and Bohemian Waxwings are the most prominent fruit-eating birds in North America. They have digestive system adaptations that enable them to thrive on sugary fruits. Cedar Waxwings are the only species outside the tropics to feed fruit to their young. As an interesting aside, the young of the brood parasite (a brood parasite lays its eggs in other birds' nests), the Brown-headed Cowbird, often die in Cedar Waxwing nests because they are unable to survive on fruits fed to them by adult Cedar Waxwings.

Cedar Waxwings consume the berries from numerous plant species. The distribution of North American Cedar Waxwing populations have grown due to human activities that include planting berry-producing ornamentals, orchard expansion, and allowing farmlands to revert to natural states. Cedar Waxwings have a mutualistic role in contributing to the success of the plants whose berries they eat by spreading seeds in their excrement.

Cedar Waxwings eat berries whole. Smooth outer feathers give these birds a silky appearance. Photo by Steve Patt.

Cedar Waxwings are especially susceptible to death from alcohol consumption that comes with eating fermented fruits. They are often killed from falls or flying into objects when intoxicated. The death of large portions of flocks from alcohol consumption has been noted in the literature.

Flocks of Cedar Waxwings raid fruit crops that are defended by other species. Species such as the Northern Mockingbird and the American Robin aggressively guard prized winter fruit crops. Robins can defend their fruit crop against fifteen or fewer Cedar Waxwings, but when the Cedar Waxwing flock exceeds 30 or more birds, the robin is helpless to stop the raid. In one case, Cedar Waxwings cleared a crab apple crop in 25 minutes when 36 birds descended on a tree defended by a robin. Although I have not encountered information on predation reduction due to flocking, I would not be surprised if this is also a factor. Raptors such as the Sharp-shinned Hawk, Cooper’s Hawk, and Merlins kill and eat Cedar Waxwings. Flocking tends to confuse predators, leading to reduced predation rates.

Cedar Waxwing and American Robin squabbling over a feeding territory by Erica Fleniken.

Cedar Waxwings rear their young in the late summer when the availability of ripe fruit is at a maximum. For the first few days, the brood receives a protein-rich diet of insects in their diet brought to them by the father, but this soon ends, and fruits become their primary food source. After the breeding season, when the young have fledged, Cedar Waxwings flock and feed on tree sap, cedar berries, fruits of mistletoe, toyon, madrone, cultivated berries, etc. Insects also supplement their diet.

Attracting Cedar Waxwings to Backyards

If you want to see more of this species in your backyard, consider planting shrubs that produce berries that they eat during the winter. See the “Birds And Blooms” link below for more information. Cedar Waxwings are susceptible to window collisions, so do whatever it takes to prevent this from occurring.

Cedar Waxwing flock bathing by Hita Bambhania-Modha.

Description

Cedar Waxwings can be identified by their striking black masks with a thin, white surrounding outline, a crested head, red wax-like endings of the secondary feathers, and the striking yellow ends of the tail feathers. The number of red-tipped secondary feathers increases with age, and some ornithologists have suggested that the higher the count of these red tips, the more attractive an individual is as a mate.

Cedar Waxwing showing 6 red-tipped secondaries, a yellow-tipped tail and its face mask by Dave Zittin.

Cedar Waxwings do not have a song, but they do have a very high-pitched whistle-like call.

Distribution

In the summer, breeding populations of the Cedar Waxwing occur across the most northern U.S. states and extend north, almost to the Arctic Circle.

In the winter, they migrate south and occur from the Canadian border south into northern Central America. During the winter, they form nomadic flocks, often seen in Santa Clara County. Their highest winter densities occur in the southeastern plains of Texas, where they feast on juniper berries.

Similar Species

The Bohemian Waxwing is the only bird on the North American Continent that looks similar to the Cedar Waxwing, but they have a more northern distribution and are rarely seen in California. Among other differences, Bohemian Waxwings have two white rectangles on their wings that Cedar Waxwings lack.

Explore

An excellent video that pretty much says it all about this species: Cornell Lab of Ornithology Video on Cedar Waxwings

Note how a pair of birds passes a food particle back and forth during courtship: Video of Cedar Waxwings courting

Hints on attracting them to your backyard from “Birds and Blooms” https://www.birdsandblooms.com/birding/attracting-birds/attract-waxwings-berries/

Listen to the high-pitched “seee” call of the Cedar Waxwing: https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/cedar-waxwing

Distribution map: https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Cedar_Waxwing/maps-range

More Backyard Bird Information

View more common Santa Clara County Backyard Birds

Visit our Backyard Birding page

Tell us what you’re seeing in your yard! Send your notes, photos, and sound clips to backyardbirds@scvas.org. We’ll feature your submittals on our website.

Banner Photo: Cedar Waxwing by Brooke Miller