What to Look For Now—Timely Birding

Spring 2021

Matthew Dodder

SCVAS Executive Director

Flycatchers of Spring

Like a lot of spring arrivals, the Flycatchers come to us from somewhere south. Whether the Tyrannidae travel north to escape the competition of their winter haunts or exploit the new annual crop of northern buzz-wings, who knows? But they come in great numbers, to raise families in every habitat we can provide. Some representatives come from as far as Brazil! They are some of many harbingers of spring and the sudden increased availability of flying insects. I’ll leave it to you to guess which Flycatcher does not make a long annual journey; you probably have one in your driveway right now.

Ground Level

Something great about the Tyrannidae is that they often have nicely defined habitat preferences. As with other large bird families, once a birder has a grasp on the preferred habitat, the list of possible species drops to a manageable number. Otherwise, we’d constantly be left with ten or more species to consider at once. Similarly, they fall into natural categories (genera) and finally, there’s timing—not all Flycatchers are plentiful at the same time of year. Take our two Phoebes (Sayornis) for example. The Black Phoebe is resident in our county and is always drawn to moisture, whether it’s a lake, a creek, or even a large puddle. The Say’s Phoebe, which is primarily with us during fall and winter, breed only very sparingly here. It has a distinct preference for dry open terrain and seems indifferent to water.

When the two species are found together, we have the perfect opportunity to observe their different flight styles, the Say’s being more buoyant and perhaps butterfly-like. Neither one of our Phoebes care much about trees and make their nests on structures (Black) or amid rocks or crevices (Say’s)—and it is usually a combination of grass and mud.

Barbed Wire & Ranch Land

Our Kingbirds (Tyrannus) are gray and yellow birds migrating from the south in search of wide air space. Instead of the fluttering, hovering, low-to-the-ground flight style of the Phoebes, these extra-large Flycatchers are aerial acrobats, rushing out from an elevated watch post in direct, almost whiplash-inducing style. Violent and not butterfly-like at all. Western Kingbird prefers the most open of surroundings— places where the gently rolling grassland and earth are interrupted by isolated trees and barbed wire—oak savanna as well as ranch and agricultural lands. Their fast-rewind-sounding call can be heard loudly in places like Coyote Valley, San Antonio Valley, Pearson Arastradero OSP, Ed Levin Park, Stanford Dish, and Grant Park.

Cassin’s Kingbird is more woodland tolerant and seems drawn to the very tall trees of wide southern valleys. It barely creeps into our county, but can be found annually. San Felipe Road outside of Gilroy is a perfect example of the terrain it likes, with its giant eucalyptus and nearby creek. The Western, by contrast, cares not for water, and is quite happy to be far from it. Despite these differences, they both seek royal platforms for their nests, either isolated trees or high-tension towers, where the view is good.

Edges & Dry Spots

The Ash-throated Flycatcher (Myiarchus) is more a fan of arid country. True, like all of these examples, it can be found away from their supposed preferred habitats, but when one gets into drier areas, where rocks and thorny bushes prevail, that’s where you’ll find this cinnamon and gray Flycatcher. It winters in Mexico and arrives here early enough to get in on the limited cavity market. It also seems to like the thicket-rich edges of each habitat. They make their nests in tree holes unlike other Tyrannidae, but they will forage over the adjacent open area using quick, short, less-acrobatic flights. Listen for their distinctive “kip-weer!” or a surprisingly convincing referee-whistled “breeet!”

Some of the spots I like to look for Ash-throated Flycatcher are Pearson Arastradero OSP, Coyote Valley OSP, and Grant Park near the ranch house, but it is a widespread western species and our county has much of the dry, edge-rich habitat it enjoys. While Kingbirds love wide open areas, Ash-throated Flycatchers prefer to forage in the areas that border open expanses, frequently nesting in abandoned woodpecker holes.

Woods & Waterways

There’s a group of Flycatchers many birders dread, the Empidonax. These are the small, greenish-yellow, greenish-gray, greenish-brown, wing-barred birds of the forest interior. Pacific-slope Flycatcher is our most common example and it is relatively simple to identify. One finds it most often along riparian corridors, but backyard gardens and park edges will do as well. If you live in a location that resembles such areas, you might find their nondescript cup nest above your porch light, or in a tree out back. Its distinctive whistled call, which sounds like someone hailing a taxi, “hurry UP!!” is common and immediately recognizable. The disjointed song is heard less often but well worth learning.

I always notice this bird’s all-yellow lower mandible and almond-shaped pale eye ring. It also has a comparatively vibrant greenish-yellow color which differentiates it from most of the other, and less common Empidonax species we get. Hammond’s Flycatcher, for example. This closely-related species only passes through our area in spring and fall as it travels either toward or away from its breeding range. Its spring occurrence in our county is mostly between March and April. If you see an Empidonax (small, greenish, wing-barred and eye-ringed Flycatcher) that you don’t quite recognize during this window, consider Hammond’s. It should have grayer plumage with a tiny black bill and longer primaries. Because it is just a “pass through” bird here, it can be found almost anywhere.

Unfortunately, both Gray and Dusky Flycatchers (pass throughs, again) are also encountered during this window, and their differences are subtle. So really, there’s plenty of room for all of us to get totally confused. Come fall, all scores will be reset to zero and we add Willow Flycatcher into our list of strong candidates. Ask me again in a few months.

Tree Tops & Conifers

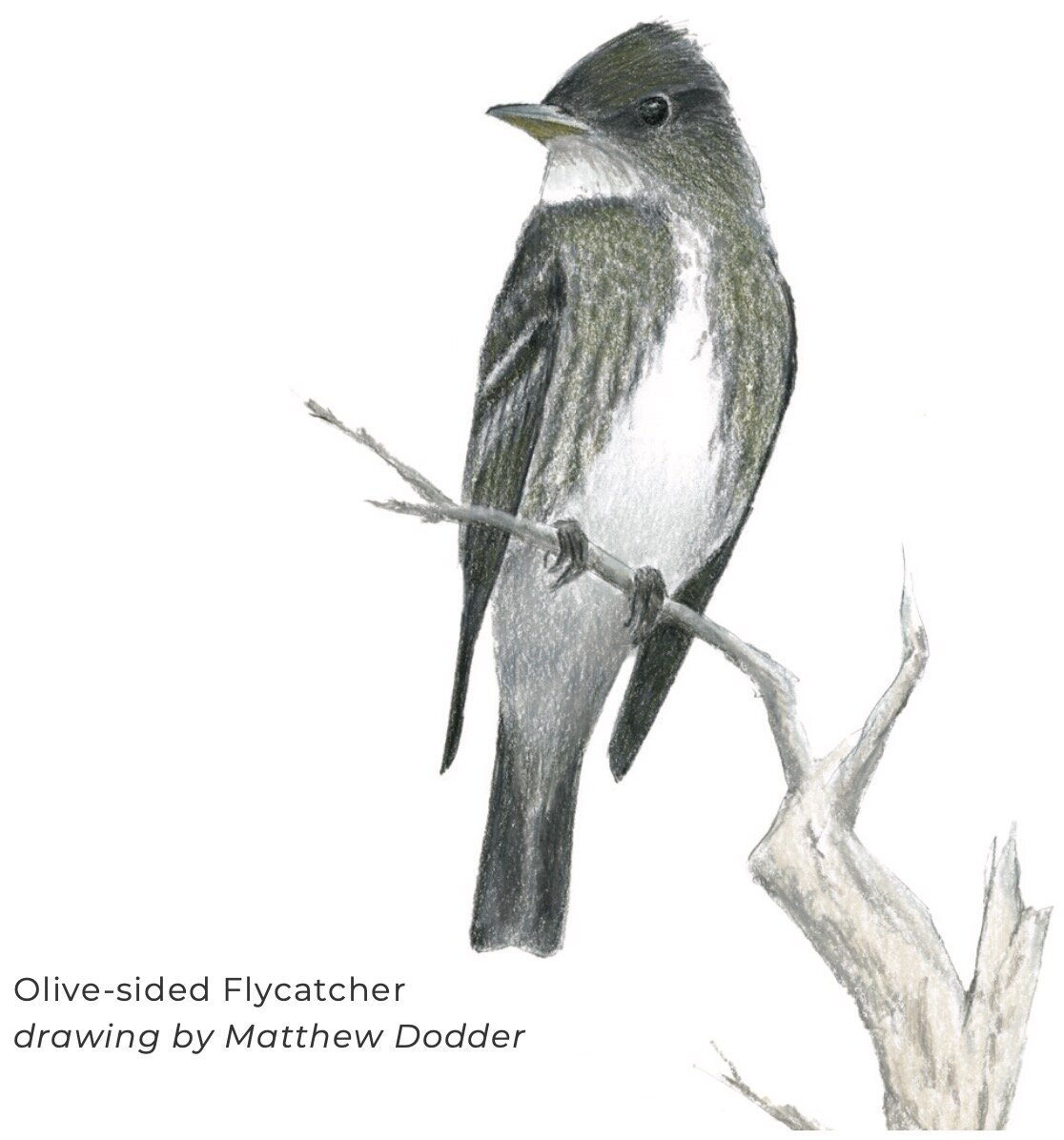

Our final group (Contopus) contains both Western Wood- Pewee and Olive-sided Flycatcher. Drab olive-drab—like the drabbest olive-drab you’ve ever seen, but drabber. They have unimpressive wing bars if they remember to have them at all, and no eye ring to speak of. They are long-distance migrants from northern South America and Brazil, and often late arrivals here as a result, but it is certainly not because they’ve dressed up. Their primaries are longer so that their flight style is somewhat intermediate between the fluttery style of the short, round-winged Empidonax, and the dramatic, fast aerial whiplash of the power-winged Tyrannus. They are notorious for picking a favorite perch from which to hawk insects.

The Olive-sided, a robust Flycatcher, enjoys the very tops of trees, especially dead-topped conifers and other snags. Its smaller congener, the Western Wood-Pewee, is usually found somewhat lower on the totem pole, and is not so exclusive to conifers. Each bird returns to its lookout frequently, so if you raise your binocs just as the bird flies away, just wait. It will likely return. Both have distinctive calls, the Olive-sided announces happily, “Quick! Free beer!” And the the Western Wood mutters hoarsely, almost under its breath, “Beer...”

So there you have it—Flycatchers of Spring! Why are they here? To survive and thrive. And as long as we hold up our end of the deal, keep our waterways clear, our grassy hills, ranch lands, old growth woodlands and thickets alive and healthy, the birds will be as well. They’ll arrive and provide a valuable service, ridding us of just enough stinging, biting buzz-wings to make life more tolerable. And they’ll challenge us to figure them out every flap of the way.

Photos at top, L to R: Pacific Slope Flycatcher Deanna Tucker, Western Kingbird Dave Zittin, Hammond's Flycatcher Garrett Lau, Say's Phoebe Peter Hart, Western Wood-Pewee Tom Grey